This is by way of a continuation of/variation on my previous post entitled “Are song lyrics poetry? Or are they philosophy?”

It has often been said that pop song lyrics are like poetry, sometimes even that they are poetry.

I considered for a while that maybe song lyrics would replace poetry in the hearts and minds of intelligent young people, but it now seems to me that if anything has been replaced in that way, it is probably philosophy. Where once we might have turned to books to find the concepts by which we could lead our lives, the great mass of us now acquire those ideas through popular songs.

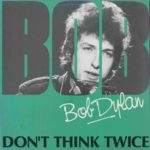

Although philosophical ideas were obviously expressed in popular songs throughout the ages, my generation became aware of it when we encountered singer-songwriters like Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen in the 1960s.

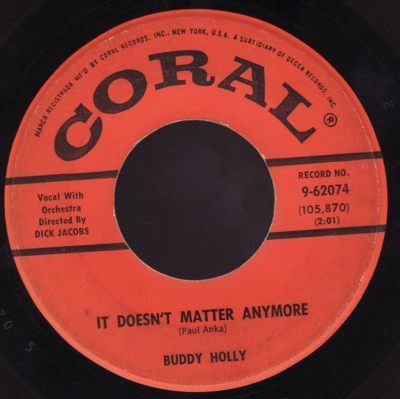

For the sake of brevity, I’ll try to focus largely on just one idea, the concept of nihilism, as expressed in popular songs. When Buddy Holly sang I Guess It Doesn’t Matter Any More (written by Paul Anka, no less) in 1958 I certainly didn’t recognise it as an expression of nihilism but, in many ways, that’s exactly what it was. It’s a song about a young man who has come to the realisation that the time he has spent on his girlfriend has been worthless because “It doesn’t matter any more.” The general idea is couched in the specifics of their relationship, so really it’s that particular girl who ‘doesn’t matter any more’, but it’s not a huge step to expand the idea from a relationship into every aspect of life. Arguably, nihilism is a negative concept because it renders all life, all our efforts and every thought and action pointless but, seen from another perspective, what it’s really saying is that no matter what we do or say, things will turn out however they turn out for reasons which are usually beyond our control.

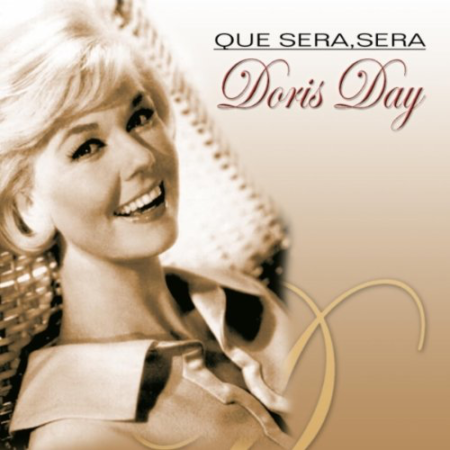

In that sense, I Guess It Doesn’t Matter Any More harks back to Que Sera, Sera, from 1956, in which a young girl asks her mother (and later her boyfriend) what the future might hold, and is told “Whatever will be, will be”. It’s a bright, happy song and, to me, it says that nihilism isn’t necessarily negative. Indeed, if we can accept into our lives the idea that we are not in control of our destinies, then we will probably lead happier lives. That’s not to say we shouldn’t try to influence the paths our lives take, but only we should understand that things very probably will not always go the way we would like them to, however hard we try.

In 1963, Bob Dylan expressed a decidedly nihilistic concept in Don’t Think Twice It’s All Right, whose opening line is “It ain’t no use to sit and wonder why babe, if’n you don’t know by now”. As with the Buddy Holly classic, the idea relates specifically to a romantic relationship gone wrong, but it’s much more of a generalised philosophical concept than Holly’s was. Dylan’s use of the term “It’s all right” can even be interpreted to mean that nothing is ‘wrong’ because whatever happens will be ‘right’.

It’s a questioning of our entire belief in codified ideas of right and wrong, asking us to use our own moral compasses to decide what we believe is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. Maybe that makes for a very uncertain world, but I believe that is the world in which we exist and the sooner we adapt to that idea, the sooner we can make some kind of progress. I like to think that there are certain things and actions which we’d all more less agree are ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, but I’d prefer for us to reach those conclusions by our own efforts rather than by simply accepting what society tells us is the case.

It’s a questioning of our entire belief in codified ideas of right and wrong, asking us to use our own moral compasses to decide what we believe is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. Maybe that makes for a very uncertain world, but I believe that is the world in which we exist and the sooner we adapt to that idea, the sooner we can make some kind of progress. I like to think that there are certain things and actions which we’d all more less agree are ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, but I’d prefer for us to reach those conclusions by our own efforts rather than by simply accepting what society tells us is the case.

Steven Stills wrote his song It Doesn’t Matter for the 1972 debut by Manassas. The relevant line here is, “It doesn’t matter which of our fantasies fail.” Again, it’s about a relationship, but the way he attaches the idea to personal fantasies makes it clear that he’s trying to express something that extends beyond the boundaries of ‘normal’ experience into the way in which we all intermingle our fantasies with our realities. Thus, given that we’re dealing with fantasies, how can any of it matter in the long run.

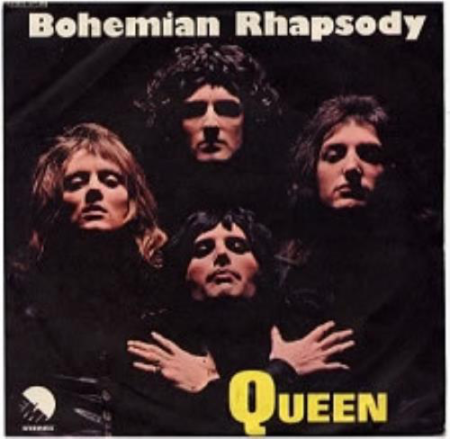

Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody, released in 1975, presents a protagonist whose life has fallen apart disastrously, leaving him in a state where “any way the wind blows doesn’t really matter to me.” This is a song which expresses the popular concept of nihilism, as an utterly negative philosophy, set against an entirely fitting tragi-comic operatic musical backdrop. It also removes nihilism from the familiar broken romance setting of so many earlier songs dealing with the subject.

By the time we reach Souvenir, the 1981 hit by Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark, the song’s writer/singer, Paul Humphries is evidently expressing his personal philosophical outlook, “It’s my direction, it’s my proposal, it’s so hard, it’s leading me astray” before stating “It’s not important now”, and then going on to explain that, although he can’t articulate precisely what he means, “my feelings still remain.” This one isn’t expressly about a failed romance, but it resonates powerfully with me as a lyric trying to get to grips with the notion that no matter what we believe, it is ultimately of no importance. Further, it points out that when logic and feelings are opposed, it is often our feelings that we ultimately put our faith in.

The preceding examples all deal with nihilism as expressed through the phrase “it doesn’t matter” but, I am generally drawn to popular music which seems to me to have some philosophical content. There’s something powerful about a song which, at first listen seems to be disposable pop but on subsequent listens reveals a little more.

Chris Rea’s Let’s Dance, from 1987 is one such. Built around uptempo rock riffs, it seems to be little more than a tale of a chance romantic encounter until we hit the line, “There’s a world, far away from the one we see” which pitches the song into a very different zone, suggestive of mysticism or even religion. I enjoy that kind of lyric writing, despite the song being saddled with what is easily one of the least relevant pop videos ever made.

A year later, Bobby McFerrin’s Don’t Worry Be Happy borrowed its title from an expression frequently used by the Indian mystic and sage Meher Baba. Thus, what sounds at first like a happy-go-lucky pop ditty designed solely as a vehicle for McFerrin’s astonishing vocal virtuosity, can be considered as a work of pop metaphysics.

BTW : I am not a philosopher, and have no wish to pretend to be. The foregoing are simply thoughts that have entered my head as a result of listening to popular music.